Advances in human behaviour came surprisingly early in Stone Age

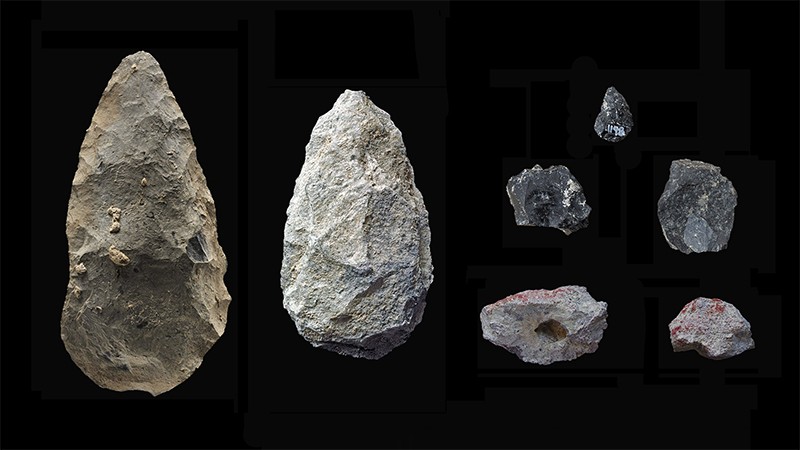

Simpler tools (left) gave way to smaller and more complex versions (right) in Kenya’s Olorgesailie Basin.Credit: Human Origins Programme, Smithsonian

Early humans in eastern Africa crafted advanced tools and displayed other complex behaviours tens of thousands of years earlier than previously thought, according to a trio of papers published on 15 March in Science1,2,3. Those advances coincided with — and may have been driven by — major climate and landscape changes.

The latest evidence comes from the Olorgesailie Basin in Southern Kenya, where researchers have previously found traces of ancient relatives of modern human as far back as 1.2 million years ago. Evidence collected at sites in the basin suggests that early humans underwent a series of profound changes at some point before roughly 320,000 years ago. They abandoned simple hand axes in favour of smaller and more advanced blades made from obsidian and other materials obtained from distant sources. That shift suggests the early people living there had developed a trade network — evidence of growing sophistication in behaviour. The researchers also found gouges on black and red rocks and minerals, which indicate that early Olorgesailie residents used those materials to create pigments and possibly communicate ideas.

A time of change

All of these changes in human behaviour occurred during an extended period of environmental upheaval, punctuated by strong earthquakes and a shift towards a more variable and arid climate. These changes occurred at the same time as larger animals disappeared from the site and were replaced by smaller creatures. “It’s a one-two punch combining tectonic shifts and climate shifts,” says Rick Potts, who led the work as director of the human origins programme at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. “That’s the kind of stuff out of which evolution arises.”

Researchers from the Smithsonian Institution and their colleagues tracked changes in the behaviour of early humans in Kenya’s Olorgesailie Basin.Credit: Human Origins Programme, Smithsonian

The studies push back the timeline for such behaviour by around 100,000 years, adding to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the roots of human culture are deeper and more extensive than once thought.

The latest evidence is “probably not enough to put the question to rest as to what effect the climate variability had on human behaviour”, says Nick Blegen, an anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. But he says that the findings from Olorgesailie provide solid evidence for a shift towards sophisticated behaviour that predates the earliest evidence for Homo sapiens. Researchers have traditionally thought that H. sapiens emerged around 200,000 years ago, but fossils discovered in Morocco could push that date to more than 300,000 years ago4.

Blagen has documented the transport of obsidian in central Kenya roughly 200,000 years ago5, and he is preparing another study that would push that record back to 396,000 years ago at the same site. The record for such complex behaviour is likely to extend back even further, he says, but it is not clear whether the environment is shaping human behaviour, or whether advances in human behaviour are enabling them to inhabit riskier environments.

Complex tools

Excavations in the Olorgesailie Basin have been turning up Stone Age artefacts ever since Louis and Mary Leakey pioneered work there in the 1940s. But this is the first time that scientists have documented evidence of more advanced tools and behaviours typically associated with the Middle Stone Age, which lasted until 25,000–50,000 years ago, says Alison Brooks, an anthropologist at George Washington University in Washington DC, who led the dating and analysis of the latest artefacts.

Isotopic dating techniques helped the team to pin down the age of the stone tools, and the researchers traced the obsidian back to its sources, which were mostly located 25–50 kilometres away in multiple directions. “It’s the best evidence yet for the exchange of raw materials” so early in time, Brooks says.

Curtis Marean, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Arizona in Tempe, says he isn’t yet convinced by the evidence for trade. “To demonstrate extended social networks, I would like to see regular and systematic transport of raw material across a number of artefact types on the order of 100 kilometres,” he says.

The team cannot say exactly how long before 320,000 years these changes happened because an extended period of erosion at the site wiped out the archaeological record there between 499,000 and 320,000 years ago.

Some information could come from several projects that drilled into ancient lake beds in Kenya and Ethiopia to collect a detailed record of environmental and ecological changes in the region6. Potts and his team drilled two of those cores in the southern Olorgaseilie Basin, and Potts says the cores cover the entire period that is missing from the archaeological record. Comparisons with cores drilled elsewhere in East Africa should help scientists to differentiate between events happening locally and broader regional climatic trends.

“The drill cores I hope will be a game changer, because of the precision of the environmental record and hopefully the precision of the dating,” Potts says. Then it’s a matter of working to understand how animals and people might have responded to the changing environment, Potts says. “Only then can we say anything about how climate is really affecting human evolution.”

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.