When Innovation and Technology Fail Us

We see technology, innovation, and the efficiency they bring as relief to our burdens, potential solutions to some of our greatest problems, such as the climate and pollution.

Could they be the opposite?

Could they, while solving immediate problems, create bigger, long-term ones?

I write the following as the holder of six patents, as well as a PhD in astrophysics, having helped build an x-ray observational satellite, still in service nearly double its slated 10-year mission. That is, I know technology and innovation. I’ve lived it. I value them.

Technology, innovation, and efficiency

We could start with any technology, but why not a big one–the steam engine.

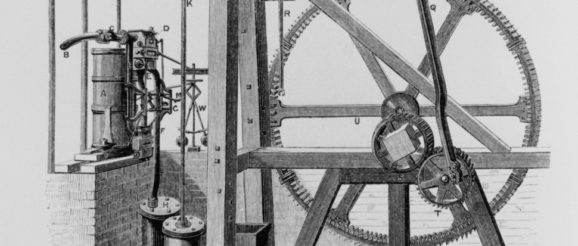

By 1776 James Watt created his steam engine that, along with other advances, ushered in the industrial revolution, which many credit with improving standards of living around the world.

Note that Watt didn’t invent steam engines. He made it more efficient.

The engine burned coal to get more coal. So more efficiency means using less coal, right?

It led to centuries of using more coal and whatever other fossil fuels we could find. Yes, each engine used coal more efficiently, but more engines existed. More engines not only served more uses, they created more uses.

Efficiency leading to more use still seems counterintuitive to many.

So did the idea that building roads led to more traffic–a lesson many cities have learned through experience, sadly too late for many to undo the devastation the roads laid on the communities they went through, often gutting.

Less than a century after Watt, William Jevons clarified and published about this apparent paradox in his book The Coal Question. He noted, in particular, that increases in energy production efficiency led to more, not less, consumption.

Many still see the pattern as a paradox, but it isn’t, as I’ll show below, from the right perspective.

Amid greater efficiency, we see more use and output. Today, our problem with CO2 and many resources is total output and use, not efficiency.

Car engines, for example, are more efficient than ever, approaching physical limits. Our problem is less that our engines lack efficiency. It’s that we have too many engines and we use them for purposes we never did before. We use 2,000-pound machines to get food from the store where we used to walk.

To call a sustained phenomenon a paradox doesn’t describe the phenomenon. It describes us–in particular, our flawed understanding.

The contradiction isn’t in the world, it’s in our understanding of it, or lack thereof.

Economists debate if this or that proposed example qualifies as an example of Jevons Paradox (or the similar Rebound Effect).

They’re missing the forest for the trees, somehow missing centuries of increased efficiency on a global level leading to increased use of nearly every industrial input. We relatively puny humans use as much energy per person as a blue whale.

Economists have the tools to resolve the paradox

The phenomenon only looks like a paradox when you look at the use you made more efficient: if you make it more efficient, how could it use more energy?

That’s not where to look.

When steam engines become more efficient, people used them not only for mining coal, but lifting things, moving things, and so on. Then people created vehicles steam engines could move, leading to more steam engines, railroads, and so on.

In other words, the place to look is the people not using the tool who will after you make it cheaper. Beyond those new users, you then have to look at entrepreneurs who will create more tools to use more. You have to look beyond entrepreneurs too, but you get the idea.

Ultimately you look at the demand curve. Here are supply and demand curves you might remember from economics class.

As long as the demand curve slopes down, meaning more Q at lower P–that is, more quantity at lower price–then efficiency will increase supply, shifting the supply curve to the right, crossing the demand curve at a higher Q.

In other words, increasing efficiency in a downward sloping demand curve increases quantity.

The same happens when you build roads. Looking only at a roads current users misleads you to think more roads will lower car density. You have to look at people not using the roads who will use them.

Efficiency creates new users.

Technology and Innovation

Technology, innovation, and efficiency helped us as long as their resulting lower prices and increased production outweighed the costs of increased use and output.

Until recently, few could conceive of a problem with problems from output. Humans being so small compared to our planet, few could have expected us to affect it on a planetary scale.

For centuries, we could even dismiss or debate the evidence that we puny humans could affect the planet on a planetary scale. Few species have done so.

Now the evidence is overwhelming that we can. No one need pretend otherwise. Even amid disagreements in some areas, say global warming, consider that we project more plastic in the Pacific Ocean than fish soon. There are extinctions, disappearing non-renewable resources, and so on.

Nobody wants mercury in their fish.

We live in a system that, according to evidence, after thousands of years of improving the human condition is verging on worsening it. We don’t know how fast it may turn.

Making a system that hurts as more efficient will make it hurt us more efficiently.

A common knee-jerk reaction at this point is to say, “Do you want to back to the stone age?”

To suggest moving backward is the only alternative is a false dichotomy. It speaks of a lack of imagination. Innovation can move in different directions.

The problem isn’t technology or innovation. They are neutral. The problem is the goals of the system they serve.

Our current cultural goals evolved based on information that’s now outdated. They were right for their times, but times have changed, as any Miami resident will tell you during their floods.

Changing elements of a system rarely changes the system. Acting on leverage points can change systems. Among the most effective leverage points are a system’s beliefs and goals.

Current beliefs I see include

- “acting environmentally is distracting” or sacrifice, or deprivation

- “What I do won’t make a difference so what’s the point.”

- “Little changes don’t make a difference and big ones take too much work.”

While I support efficiency gains, I recommend them after changing your beliefs driving them.

Try this experiment, which costs no time or money. You don’t have to tell anyone you’re doing it.

For a week, try adopting mental models or beliefs that promote stewardship, conservation, and preservation and improving your life and community. For example:

- “What I do makes a difference,”

- “Acting as a steward helps people I care about,”

- “If I act others will follow and thank me for it,”

- “If I lead in this area, my leadership experience will help me get promoted,”

- “Acquiring less stuff will make me feel more free.”

I bet you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how your perspective changes and you feel enabled and positive.

- Technology and innovation that make a polluting system more efficient pollute more efficiently.

- Centuries of data show this trend, which continues in our latest, most cutting-edge innovations, yet most people think the opposite.

- The demand curve shows why efficiency increases consumption.

- Changing the goals of the system first will create a culture where efficiency helps.

Try the experiment above and see if you find yourself changing your behavior to pollute less without technology. I predict you’ll save money and time and create mental freedom.

You’ll likely see technology differently too.